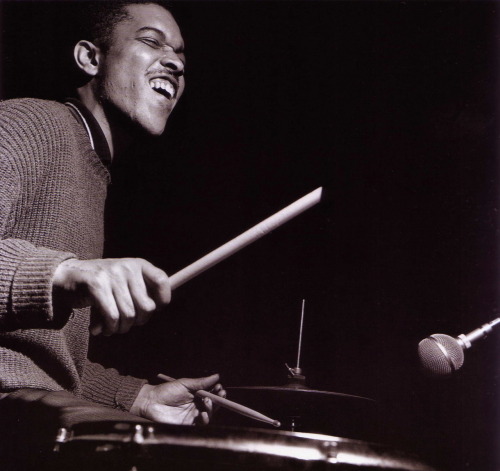

My teacher (the great Chuck Redd) recently introduced me to a slick new way of playing the bossa nova that he picked up from listening to Grady Tate. You can clearly hear and see Grady's Bossa at 7:58 in the video below:

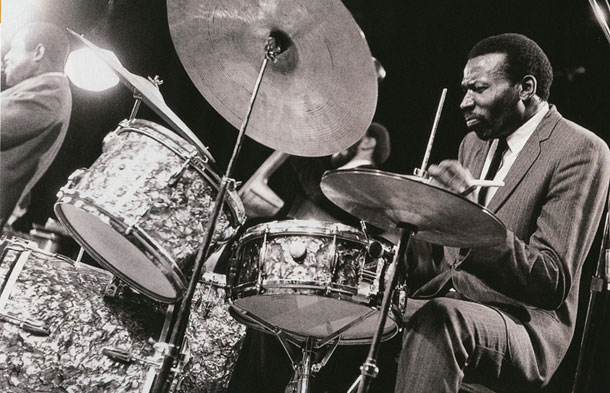

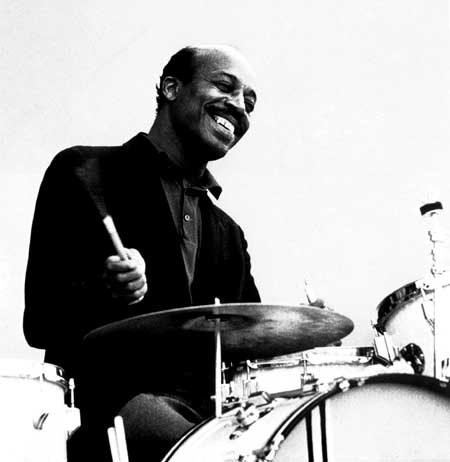

|

| Grady at work |

Here is what the basic groove looks/sounds like:

Step 1: Orient your ear

This step is reasonably self-explanatory but also surprisingly easy to overlook. You need to know what a groove is supposed to sound like in context, so find some good recordings and dive in. I would recommend a combination of really mentally engaged listening where you are trying to actively pick apart the groove, as well as more passive listening to let the overall sound wash over you. For the Grady bossa, the song "O Grande Amor" from the Stan Getz album "Sweet Rain" is perfect:

Step 2: Get it in your hands

This step is all about the physical feeling of the groove, mastering the technique and coordination necessary to play the groove. One really helpful tip with this step is get a lot of this work done away from the drum set. This will help you use your actual time at the drum set more efficiently as well as open possibilities for more flexible practice.

Here is an example of me practicing the Grady bossa away from the set:

Once you feel good away from the drums, it is time to work out the basic groove on the drums. Chuck has hipped me to practicing at 100 bpm, as this is a very challenging "in between" kind of tempo that tends to either rush or drag. Check out the video of me playing at the top to hear what this sounds like at this tempo.

|

| Ol' Faithful |

In order to get at some of these rhythmic possibilities, I like to use Syncopation to experiment. Here is a video of me playing through the first couple of lines of page 34 in this fashion again at 100 bpm:

In the subsequent posts in this series I will discuss more steps to getting beyond a beat, so stay tuned!